Kath Thomas

Script supervisor

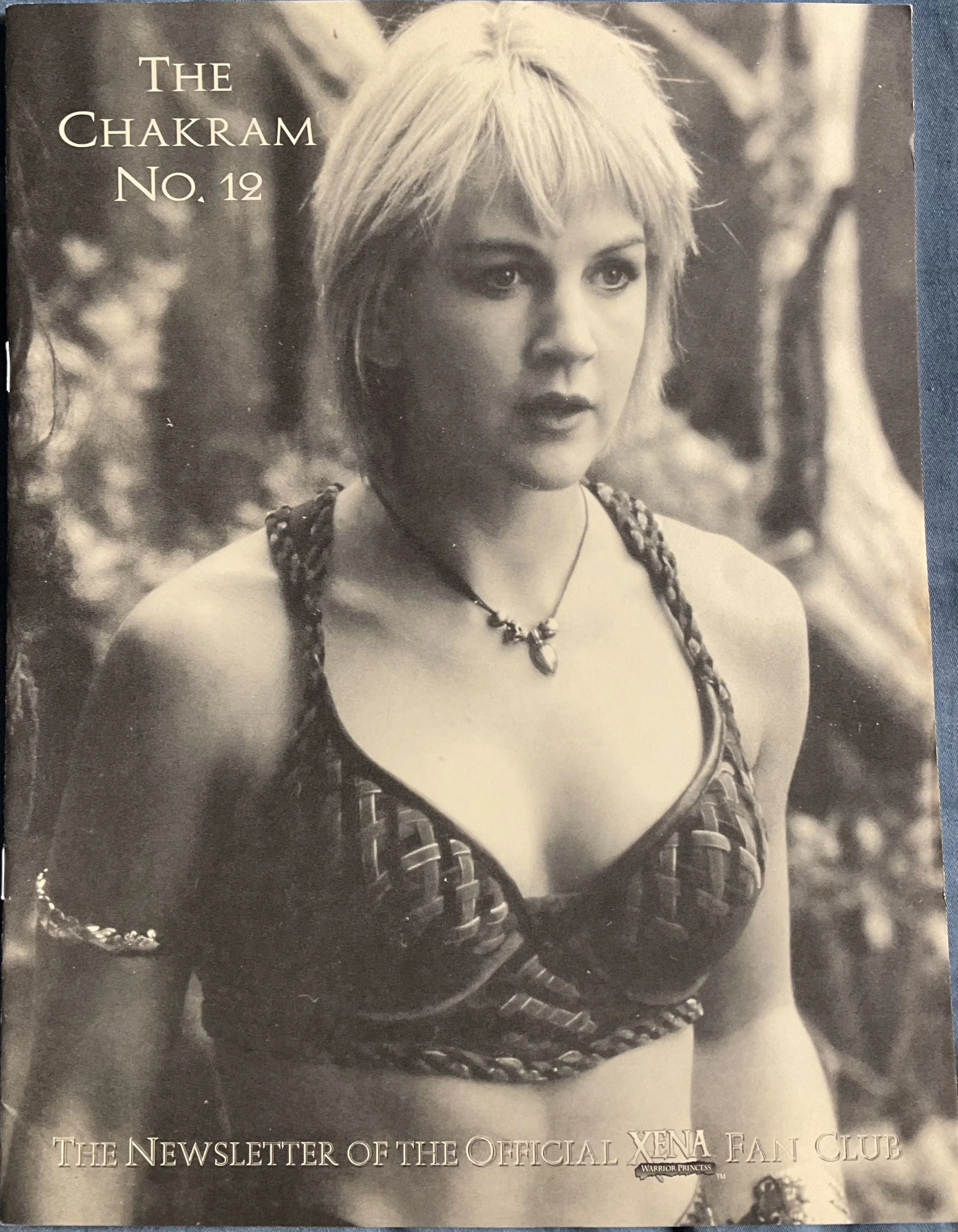

The Chakram Newsletter: Issue 12

SD: Where does your job start?

Kath: I start out reading the script two or three times.

SD: Is this the shooting draft?

Kath: I might fly through the beat sheets and do a quick draft, but I don't get serious about any script until I see the words “shooting draft” on it.

Next stage I time the script

SD: How do you do that?

Kath: Partly from past experience. Beating out the action and drama. Reading the dialogue - if you know the cast you’re familiar with their pace. You read through a scene and you picture it in your mind. This is prior to having spoken to the director so there’s always room for, “How is he going to play this shot?” It all has to do with piecing the beats together. After a while, you know if you hold on a certain scene, the audience will be bored. So you only use a couple of beats. Another scene is a hero (lead actor) shot, it's more interesting and that’s where the money is, so hold that one longer.

SD: I pictured you in your house acting it out like a play.

Kath: That's exactly what I do. There are even occasions when I get my kids involved acting out parts. “I’ll be Xena. I’ll be Gabrielle.”

SD: And the rhythm of an actor's speech plays a part. If you've got Jimmy Stewart, you know it's going to go a whole lot slower.

Kath: In terms of quantity, there's a rule of thumb that a page is about a minute. That doesn't just apply to our scripts. That's across the board in the industry. A script is about 45 pages long. And you need to notice if some of them are half pages.

The script for “Ides” is 41 pages and it timed out to 41 minutes, 20 seconds.

SD: And after the timing, what comes next?

Kath: Then I do a breakdown which is a very broad look at the script. You look at the the believability aspect in the sense of if it takes two days to get to a location in the story, it can’t take a half day to get back. You check that type of geography in the story.

Generally a breakdown is a critical look at the content. Does it make sense? Does it have a flow to it? If we go from scene one through scene two and three and we have Xena in scene one and we pick her up in scene two and she’s not in scene three, we need to make sure at the end of scene two we know she’s gone somewhere else and we’re not expecting her to be in three. Trace the thread of the story and make sure it isn't broken.

Then we check details of cast in each scene. Where do they come from and go to? That’s what I'm working on at the moment. For example, I note a character’s name and every scene they are are in, what they are wearing, carrying, using, etc. I note props, actions, location of characters in a scene and so on. I make lists of every piece of information that might be needed because once you’re on set, the idea is to be able to access the information immediately.

I note the timing of page count per scene. I note broad aspects of wardrobe, makeup and art and then correlate information with those departments. They each have their own detailed breakdown of what they’re doing for the episode.

SD: So that if a character sits down holding a pair of blue and white shoes in their left hand, they need to stand up holding the same shoes in the same hand even if the action is filmed on another day.

Kath: It’s because we do shoot out of sequence that we need to track all of the details. Maintaining the thread of believability is vital.

SD: So all this is before actual shooting starts?

Kath: Yes.

SD: And then once you get on set.

Kath: The first thing is the block through of the scene. Mapping out in broad terms the shape of the scene.

SD: Do you start writing things down at that point?

Kath: No, I watch where the players move around the set so we can look at the shot list the director’s drawn up and how he’s going to link the sequence of action and dialogue together and make it believable to the audience. If there’s anything jarring in that area, it becomes more obvious when you’re rehearsing. Things like eyelines. If Xena’s ridden off to the north and north was to her right in her closeup, then you have to make sure when the reverse angle is done on the person she's been talking to, that they watch her ride off in the same direction. Shooting out of sequence means all those types of things have to be notated for reference if the reverse angle is shot at another time.

SD: And after the blocking?

Kath: After the blocking, is when the camera and lighting departments take the floor over and set up their equipment. I’ll be checking over the paperwork at that point to be ready for the next shot. Then they rehearse which is walking through the movements with the dialogue added. Then we shoot the scene.

During shooting is when the script supervisor really comes into play. Anything you say that has been commited to film that the editor would then go on to use, that's where you make detailed notes of specific things that happened during the take.

You can do three and four takes, but what I detail is what has actually been commited to film. I keep my script as clean as possible until a take is designated for printing.

During the take you're watching various things like screen direction, eyelines, cutting points, when you’re out of that shot and into another. That’s important because actions at the end of one shot need to match actions done at the beginning of another. A scene which is continuous in the final show is usually shot in smaller pieces.

The cutting points are vital because my overall position is to be the link between the director and the editor. You’re the director’s advocate and as objective as possible.

SD: I've been in the editor’s room

Kath: I haven’t. (laughs) I'd love to.

SD: They're quite small. (laughs) They have a big book of the script with vertical lines drawn all over it. Is that from you?

Kath: Yes. That’s called marking up the script and it's vital. Here are some sample pages. Each time we turn over, I will mark a line on my page marking which scene it's from, what shot in the scene. A shot meaning a take of the same action. You might have two or three takes or shots of that action. The slating (clapboard) is also the script supervisor’s call. That's how we reference our shots. Because referencing information is vital if people are going to find a specific take and we have certain codes that both we and the editor’s use to notate the take.

What else will be marked down are timings of the take, when Xena turned left, if her hand was down by her side on a certain word. You don’t have to be absolutely fastidious about that but you need to know when that information will be important. Again, this has to do with cutting points. If you zone in too much on every little move, you can lose your general overview. You have to learn when it's important to be that detailed. That comes with experience.

SD: You take photos? I see you have a photo of Renee’s feet with decoration on them.

Kath: Yes, for reference. We turn all this information over to second unit for continuity. For example the script doesn't say Xena takes a knife out of her armor where it's been hidden, but she has it in a later part of the scene and we'll need a shot of her taking it out so we know where it came from.

And we also keep a running time total. If we need to drop scenes or run overtime, that will have an impact on the screen time. That's something Eric (Gruendemann) and Chloe (Smith) would have to know. And that has to do with the fact that we have to produce, say, 42 minutes of screen time exactly.

If it looks like that might be a problem, that's one thing we need to get onto while you've still got time to make changes. You might cut a fight short or drop a scene if you’re running long or embellish a scene if the timing is short. You don’t want to do too much long, slow panning in an action show. And if you’re running over and have to cut too much, you may lose the flow of the story. This is something you have to keep an eye on all the time.

And at the end of the episode, this is the book that gets sent to Los Angeles for the editor to use in putting together the show.